Written by: Janay Richmond

Date: March 21, 2020

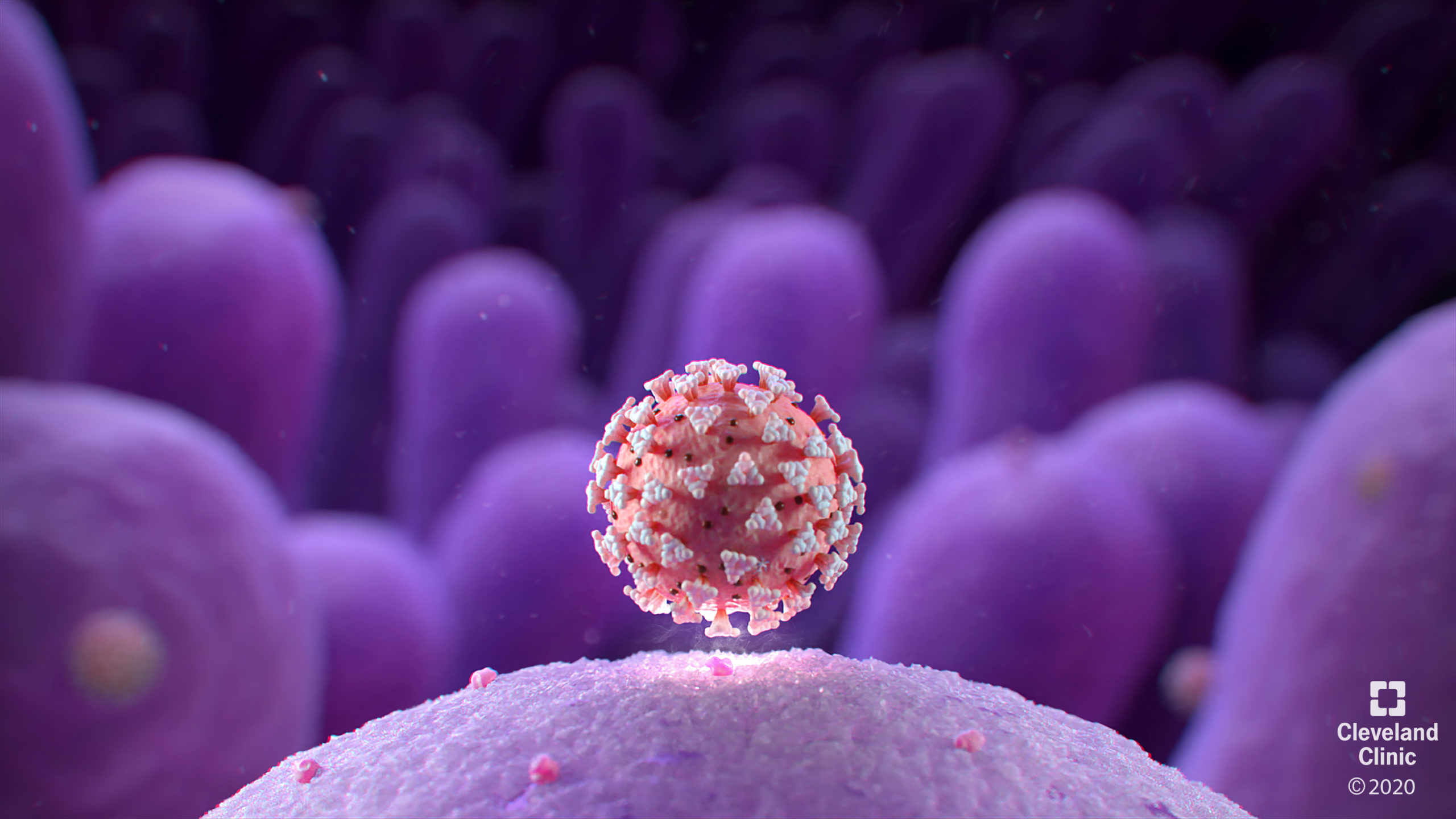

Over the last several weeks, COVID-19 has further exposed the gaping holes in our social safety net that many NCRP nonprofits work tirelessly to address on a daily basis.

As communities begin to craft solutions to help keep Americans economically and socially afloat during the immediate weeks of this crisis, it’s important that decision makers listen to those closest to ground to ensure that the current crisis doesn’t amplify existing inequitable distribution of philanthropic resources in the nonprofit sector.

Meeting payroll and community needs

Nonprofit members who reached out to NCRP say they are foremost concerned with their ability to stay financially afloat and serve their communities.

Small organizations that are led by members of historically marginalized groups who are dependent on grassroots membership networks are especially worried about coping with the brunt of the increased demand for their work as their face-to-face capacity decreases.

Debra Watkins, founder and executive director of A Black Education Network, points out that unless it is directly addressed, those who have been historically left out by foundations and other grantmakers will bear the brunt of the immediate and long-term economic and social impact of the pandemic.

“There is an old adage that states: ‘When white folks get a cold, Black folks get the flu.’ This virus is wreaking havoc on the world, but it is poor people who are suffering the most,’ said Watkins. “While some non-white-led organizations have been around for decades, they’ve never had the full support to be able to build up their cash reserves. Sadly, that is primarily due to racism in philanthropy. The question for us now is whether we will continue that narrative or have the courage to deliberately create a new one.”

Amy Sausser, director of development at the Advancement Project of California, is grappling with the fact that, as each day passes, so does the chance that additional costs will eat into shrinking revenues. Practically speaking, that means having to worry about losing security deposits for revenue generating events that might be canceled or seriously impacted by the response.

“If, heaven forbid, the virus is still impacting gatherings, we will lose our security deposits,” said Sausser. “I suspect many orgs are struggling with this, especially for events happening this spring.”

Adrianne Johnson, vice president of development for Faith in Public Life, agrees that there is a need for more support to absorb the financial losses that might come from canceling events to non-refundable business expenses like travel or conference registrations.

She and others like Ohio Voice Executive Director Gavin DeVore Leonard are also concerned about meeting grant deadlines and deliverables particularly as it relates to programmatic work that is dependent on person-to-person meeting and organizing. Census outreach efforts face an especially daunting task as small under-resourced community efforts try to pivot quickly to digital or alternative solutions.

“Our core programmatic work – census, harm reduction, voter mobilization and all of our state-based work – is relational. We hold in-person gatherings, meetings, trainings and disseminate information and messages to other people in faith gatherings (church, mosque, etc.),” said Johnson. “Nearly all of the tactics, not just ours but across the Census Get Out the Count stakeholders, are based on in-person contact either at community gatherings, events or going door-to-door. Even if coordinators and pastors are disseminating information and providing places for people to do the census online at churches, it won’t be impactful if people stop going to their places of worship.”

“We’ve heard concerns about whether funders will hold organizations accountable to goals on programs they don’t feel are safe at this moment, so we’re hoping that funders will come out clearly and ease those concerns to ensure health and safety are put first,” said Leonard. “Our hope is that funders will consider rapid response investments to help ensure field-necessary programs like voter registration, ballot signature gathering, and election protection can still reach goals, as well as resources to aid the transition to digital – hardware like tablets, phones and computers, as well as software, apps and more.”

Tech worries & costs

In additions to staying open, many organizations were struggling with the equipment and training costs of operating remotely and, in some cases, having to digitize their work.

Bambie Hayes-Brown, president and CEO of Georgia Advancing Communities Together, says that one of her biggest needs is around technology. Not only does she need funds to cover everything from laptops and tablets to microphones and web cams, but she also needs money to cover the infrastructure costs for hosting virtual staff and community events.

“We have had numerous meetings and events canceled in Georgia, primarily in Atlanta,” said Hayes-Brown. “We are researching virtual meeting platforms and this past week had to cancel an in-person annual membership meeting. Our budget is taking a hit because of the unexpected expense of having to find a virtual platform.”

For many organizations, some of this tech has been seen as needed, but just simply out of reach. Sausser empathizes with organizations who are now scrambling to pay for additional tech costs that they could never really afford.

“Unlike many organizations, we are well set up for this, “said Sausser. “But if we weren’t, there would be a huge unanticipated equipment and IT consultant costs [to absorb]”

Having the technology to work remotely doesn’t automatically mean that all staff know how to use it in their daily workflow. It’s one thing to attend a webinar, it’s quite another thing to conduct your whole work routine via Zoom. It’s also one thing to work from home if you are single and quite another if you are managing a household that may have several kids attempting to virtually learn.

“We are still looking for resources to help our staff and network adapt in this crisis,” said Johnson. “How will parents with kids at home be impacted and how will our workflow over the next 2 weeks or longer need to shift? Just as important for us is how can we adequately support our network of faith leaders in their advocacy efforts and their mental health as more people practice social distancing and isolation.”

And that’s assuming that everyone literally speaks the same language or has the same hearing or visual capabilities.

“There is definitely a need for training around best practices for creating inclusive, multilingual conference calls and other virtual gatherings,” said African Communities Together Executive Director Amaha Kassa. “Providing this alongside mini-grants for tech needs like teleconference equipment, captioning and premium conference call service instead of freemium options will help ensure that we can continue to communicate and collaborate past the immediate moment.”

What should grantmakers do?

Just like #COVID19 poses the gravest threat to the vulnerable among us, it will have the gravest impact on nonprofit organizations who serve and are led by vulnerable people. As foundations assemble their response plans, they must ask themselves: How many small, under-resourced nonprofits will have the support – financial and otherwise – to sustain an all-remote workforce, to meet the health care needs of their staff and their staff’s families, to cancel events and weather other disruptions to their work for several months?

This is an opportunity for philanthropy to make up for the past. NCRP’s Pennies for Progress report showed how in the decade that ended in 2013, foundation support for America’s marginalized communities grew just 15% as a share of all grantmaking.

Support for long-term change strategies proven most effective at improving the lives of the poor did not increase at all. Among the nation’s largest 1,000 grantmakers, less than half the impressive growth in grantmaking between 2003 and 2013 was directed to underserved communities, and just 1 out of every 10 of those new dollars was for long-term systemic change strategies.

For many members, doing better this time starts with reaching out to your grantees to see how you can support them over the next several months. Reassurance might also mean being flexible around grant deliverables or even allowing funds to be used to cover tech costs and other general operating costs. It might also mean leveraging your community influence to ensure that local government provide the same kind of spending flexibility that sector grants should also provide.

Fortunately, leading foundations are listening and uniting to encourage practical solutions. As NCRP’s President Aaron Dorfman writes with Ellen Dorsey of the Wallace Global Fund, now is the time for philanthropy to give more, not less.